Exiting Eden

Fabric, wax, dyes from rust, flowers and insects, pins, wood, paint, glue, plexiglass, plaster. 2025. 55 x 25 x 7″

The most sacred sacrifices were made in gardens.

Adrienne Herndon

Clothing Remnants from dresses, a robe, lace, beads, gold leaf, ink, henna, acrylic paint, antique hanger, plexiglass, mahogany, writings from Adrienne Herndon. Herndon, Adrienne McNeil. “Our Work in Elocution.” The Bulletin of Atlanta University, May 2, 1897. Herndon, Adrienne McNeil to Booker T. Washington. (February 12, 1907): 216-17. In Louis R. Harlan and Raymond W. Smock, eds. The Booker T. Washington Papers, Urbana:; University of Illinois Press, 1980.“Life Works Opens for Southern Woman.” Boston Traveler, January 25, 1904. Edited with an introduction by A.C Cawley. Everyman and Mdieval Miracle Plays. New York: Dutton, 1959. Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Edited by A.R. Braunmuller. New York: Penguin Books, 1999 . Special thanks to the Nexus Fund the Atlanta Contemporary. 74 x 74 x 4.5 in. 2025.

Adrienne McNeill Herndon was an actress, professor, architect, and the wife of Alonzo Herndon, Atlanta’s first black millionaire. At an early age, she showed a considerable amount of promise as an actor. Born with fair skin, she hid her mixed heritage on the stage. Her desire was to star in all of Shakespear’s plays. She commenced this undertaking, but soon ran into prejudice, and her career was cut short. She returned to her home in Atlanta and received an academic position at Atlanta University, as a professor of Drama and Elocution. She brought Shakespeare and a rigorous standard of elocution to Atlanta University, performing Shakespearean plays each year, at commencement.

She designed her home, which still stands today as a museum in Atlanta: the Herndon house. It is unique in many ways, with a terraced roof which was meant to be used as a stage for performances. Her home is rich with symbolism and reminders of her heritage, as she and her husband forged a future together. In the Herndon home, mahogany wood adorns the walls, with beautiful carvings that have been worked by skilled black artisans. It is a home that is engulfed by culture and the highest society of its day. In Adrienne’s music room, soft pink walls are framed with white and gold embellishments.

The home, in all its luxury, retains reminders of the past. For example, every room has a fireplace, some with cooking pots hanging in them. These do not provide heat for the home or for food preparation. They are reminders of humble beginnings and of slavery. A mural stretches the border of the ceiling in one room, illustrating a symbolic journey of Alonzo’s life: born into slavery, and his rising into an abundant, successful life. Adrienne’s design of this home is almost a set designed for living theater. Her thoughts of how one moves through the home, the symbols, the beauty, and the ability to contemplate and express the past are all read, as one moves through her home.

Adrienne’s dress is made from the fabric of multiple dresses, which were found at vintage stores, and include a wedding dress, woman’s vintage night gown, laces, and beads. The text on the dress includes Adrienne’s own words from articles she wrote or quotes from newspapers and her letters. Much of her writings talk about her work in elocution, the study of expressive speech, pronunciation, and articulation. Texts from plays in which she starred, such as Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, and a play named ‘Everyman’, are also included in the dress. The words flow on the dress like calligraphy, reflecting the concerns of style, beauty, and expression, which were so important to her career. The hanger is vintage, made of brass. It was found on a luxury cruise ship from the 1900s. Her dress is not dyed. It is left white so that words can be the dominant feature, as they were so important in her life.

Helen Douglas Mankin

Cotton fabric, remnants of clothing from a womens wool suit, a wedding dress, and a linen table cloth, buttons, ribbons, wax, thread, ink, iron, onion, marigold, pine bark and synthetic dyes, plexiglass, pine, writings and interviews from Helen Douglas Mankin. Helen’s own accounts of her westward journey by automobile in her beloved “Maxwell” as appearing in the Atlanta Georgian between May and November 1922. Various excerpts from interviews from Helen, source: Spritzer, Lorraine Nelson. 1982. The Belle of Ashby Street : Helen Douglas Mankin and Georgia Politics. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. Special thanks to the Nexus Fund and the Atlanta Contemporary. 68.5 x 68.5 x 5.5 in. 2025.

Helen Douglas Mankin was a politician, lawyer, wartime ambulance driver, thrill seeker, and explorer. She was the second woman from Georgia elected to the United States Congress. She was among Georgia’s first women attorneys-at-law. She and her sister, Jean, trekked across the North American Continent in her beloved Maxwell automobile, setting the 1922 touring record for women drivers. She was the second wife to Guy Mankin, and the step mother to his son by the same name; two men rallied around her as she ran for public office. Helen never felt like the weaker sex and was never threatened by traditional gender roles. She believed in pushing boundaries in politics, her employment, and her adventures. She was fearless in doing all things. She was a force to be reckoned with. She was an advocate for the working class and black community.

At the outset of her political career, Helen Mankin bought one suit for each campaign and wore it every day, for luck. This work represents one of those dresses: full of wear from a life of service and adventure. The suitcoat in this artwork is worn, tarnished with iron, pine, onion, and flower dyes. A corsage is pinned to the lapel. The dress is made from clothing remnants from local thrift stores: a woman’s wool suit, a wedding dress, a linen table cloth, cotton fabric, buttons, ribbon, hanger. Encircling the rings of the outer skirt are excerpts from Helen’s life. The lines come from her road trip with her sister across the North American continent in 1922, as recorded in various newspapers throughout the United States. After seeing much of the world (including her service in World War 1) she felt beckoned home to Atlanta, to be surrounded by her beloved loblolly pines. The rings of text in the dress continue with words from her time as a US Congresswoman and her battle for reelection in 1948.

The bottom layer of Helen’s skirt is made from simple cotton cloth. This skirt is full and tightly ruffled. Helen was elected to congress through overwhelming support from the black community. Although she won a large majority of the vote, she was taken from office through a racist-era voting system rule. This essentially silenced all of the votes cast for her. In this simple underskirt, wax words resist the rust dye, which reveals Helen Mankin’s name over and over again –written in, and counted out– echoing the black vote, the silenced majority. This underskirt upholds the dress, as the voters uphold their representatives, but it is also hides the votes cast and thrown away by a racist system. Her skirt opens, as the dress tries to reveal their muted voices.

Bazoline Estelle Usher

1892 Bible, recycled blouse, cotton cloth, henna, chalk, marker, ink, wax, rust, soil from Walnut Grove, Georgia, burnt edges, button, cosmo flowers, wire, plexiglass, red oak, writings and interviews from Bazoline Usher: Black Women Oral History Project. Interviews, 1976-1981. Bazoline Usher. OH-31. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Bazoline E. Usher papers, MSS 1239, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center. Special thanks to the Nexus Fund the Atlanta Contemporary. 74 x 74 x 4.3 in. 2025.

Education was at the center of Bazoline “Babeen” Estelle Usher’s life. She was born in Walnut Grove, GA and started school at the age of four. Clinton Browning, her great-grandson, shared a story illustrating her persistence : One morning, as Bazoline was on the way to school, she saw a man hanging from a tree. The adults quietly took him down and prepared him for burial. Despite these hardship, she pressed forward and still went to school. Bazoline was taught that if you didn’t show up, you would lose your seat and couldn’t return and learn. This determination remained a theme throughout her life.

Pushed by a desire to educate their children, her parents eventually made their way to Atlanta, where Bazoline enrolled in high school at Atlanta University under the tutelage of W.E.B. DuBois. She lived through the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre and witnessed extreme discrimination because of Jim Crow laws. Later in life, she said that there wasn’t anything that she could do about the discrimination and unequal treatment in Atlanta. Though she felt unable to transform policy, she remained unsinged by the fires of bigotry around her and took advantage of every opportunity to increase her education. When such opportunities were not readily available, she said, “If you can hear (the teacher’s) voice, you can learn”. Bazoline always kept her ears open to education. In every setting, she excelled. She was salutatorian of her class, the first principal of an all-black faculty and student middle school, and the first African American to have an office at City Hall in Atlanta, where she served as Director and Supervisor of Negro Schools. She started the first black Girl Scout troop in Atlanta, she was an athlete, and a founding member of the Uplifters Club at the Friendship Baptist Church, the olderst Baptist church in Atlanta, where she also served as the Sunday School Supervisor. She was associated with W.E.B. DuBois, the Alonzo Herndon Family, Mernard Jackson, and many other influential people of Atlanta. She witnesses 106 years of Atlanta’s history.

Bazoline was small in stature. She never married, but cared for many, including her mother and her adopted niece. Throughout her life, she witnessed and was part of the changes that took place in Atlanta’s school system, growing to provide education for all. Her steady patterns of learning and filling her life with service radiated, like a mighty oak, creating a lasting impact on society.

Bazoline’s dress is made from cotton fabric, an old bible, and a blouse. The edges of the fabric are singed with fire, suggesting a pheonix rising from adversity. The patterns and lines of the fabric are drawn with melted wax and chalk. A tiny bodice lies at the center of the dress, radiating the text of her words outward. The text consists of interviews and journals: words from Bazoline. Her words are marked, inked, and stained into the dress. Bazoline’s dress is supported and uplifted by the Bible, whose pages create the outermost layer of the dress. The entire work rests inside an oak frame, representing the structure and foundation Bazoline provided for those around her.

Keep Like They Have Kept

Embroidered handkerchiefs, clothing remnants, lace, and other mixed cloth. Marigold, onion, rust, and rose dyes. Walnut wood, river birch bark, leaves, metal, inks, wax thread, plexiglass, wood backing, acrylic. Writings and love letters from Mary Pratt Parish 1909-1989. 60 x 60 inches, 2024.

This work was created for a client in honor of their grandmother, Mary Pratt Parrish. The “tree rings” are from writings that include interviews, love letters, and personal history from Mary, who was born in Mexico and exiled to the United States during the Mexican Revolution. Marigold, rose, and rust dyes were used, all symbolic in nature, of the places Mary lived. Site-specific materials were gathered from her home to incorporate into the artwork. The work’s title comes from a letter to her husband, “When they first came, they were tiny buds, but now they have all opened clear out. I have never seen flowers keep like they have kept.”

The Burnt Edge

Cotton fabric, wax, hanger, burnt wood, census, birth, and death records for Marie Kraus 1867-1914. Roughly 7 feet in diameter, 2020.

This handmade dress has been made to resemble a cross-section of a tree. Encircling the dress are census, death, and birth records for Marie Krause, the artist’s great-grandmother. Little is known of her history. Evidence of her trials and triumphs is not apparent. Who she was can only be broadly decoded through existing public records. And yet, she is still a part of the artist. Knowledge of her is lifeless without any memories that have been saved or preserved. The interaction between the past and the present, the artist and the subject, is lost. One can only scramble through the ashes to gain understanding.

I am Surprised We Didn’t Meet Sooner

Journal entries from artist’s mother, cloth/clothing remnants, oak gall, rust, soil and other natural dyes, ink, wax, thread, hanger. 77 1/2 x 73 1/2 x 4 1/4 in. 2024.

The artwork is a garment of the artist’s own making, dyed in rose hips, rust, acorn, oak galls, and onions, inscribed with words encircling a bodice, similar to tree rings. The text is from the journal of the artist’s mother, Susan Russ Crockett. The writings, penned in Lindsay’s hand, tell stories about her mother, unfamiliar to the artist. This work explores the strengths and struggles given from one generation to another and how one might pivot from what they have been given. The title comes from a journal entry recounting how her mother and father first met, “Looking back, I was surprised that we didn’t meet sooner.”

Knew They Would/Knew You Would Be Here

Cotton fabric, cedar wood, ink, hanger, Sarah Pea Rich journal entries 2814-1893. 96 in. diameter, 2020.

In the work Knew They/You Would Be Here, the journal of the artist’s relative, the Latter-Day Saint Pioneer Sarah DeArmon Pea Rich, is written in a circle to resemble the rings of a tree. The title of the piece comes from Sarah Rich’s first encounter with missionaries and the Book of Mormon. “I asked the company to excuse me for the evening, and most of the night I spent reading that book. I truly was greatly astonished at its contents that it left an impression upon my mind not to be forgotten.” Six weeks after this encounter, Sarah had a dream that the missionaries returned to her home. She told her parents that she was sure “that they would be here.” The missionaries fulfilled the dream, and she was baptized. In the process of writing out her words onto the dress, the phrase “knew… would come” aligned naturally, emphasizing her complete trust in God. Not only was she testifying her faith in the Book of Mormon and personal revelation, but she was bearing witness that God works through revelation and fulfills His words.

Taken Away

Cotton, wax, death records of Spanish flu victims from Manhattan 1918, foliage from Manhattan, wood. Used in the performance festival: Art in Odd Places 2021:Normal, 2021

The work Taken Away was performed at Art in Odd Places 2021: Normal. Written on the dress were the names of individuals who died from the Spanish flu in Manhattan in 1918 over a three-day period. The names, written in wax, were revealed by rubbing foliage collected from the sidewalk cracks in Manhattan. The names have never been archived as a comprehensive list of the victims of that tragedy; the data was collected by combing through individual death records.

Excerpt from the artist’s statement in the Art in Odd Places 2021: Normal exhibition online catalog:

There is a layer of sorrow embedded in the soil. In 1918, the Spanish Flu killed an estimated 675,000 people in the United States. The echoes of their tragedy, almost silent before, are suddenly deafening. Because once again, our country is mourning. I was asked to participate, alongside 65 artists from around the world, in a performance art festival in New York City with the theme normal. Normal today means loss of people, habits, opportunities, and the ability to mourn communally. I began to think of healing that could be done through ceremony. I gathered names from death records in Manhattan. In September 1918, there seemed to be a kind of hesitancy about what was happening. A month later, the epidemic couldn’t be ignored.

October 12, 1918, causes of death: influenza, Spanish flu, epidemic flu. I watched it ravage through families and communities. It didn’t exclusively prey on the weak, but those in their prime. The same generation that was already giving its lives to “The Great War.” Today, all of us have had loss. In times when we are not able to gather and mourn together, how can we receive healing?

In May 2021, I cradled a white dress in my arms as I walked down 14th Street in Manhattan. The dress held the names of victims of the Spanish Flu who died in that borough, written in invisible wax. I spread the dress on the sidewalk and rubbed gathered foliage onto it, leaving the green pigment on the dress and exposing the names of those who died in the previous epidemic. I believe there is healing in remembering, in understanding the dirt we stand on, in understanding that we will return to the earth. We sow our own layer of sorrow for our posterity.

Iris

Irises, satin, thread, rabbit skin glue, glass, wood, 37.5 x 45 x 2 inches, 2024.

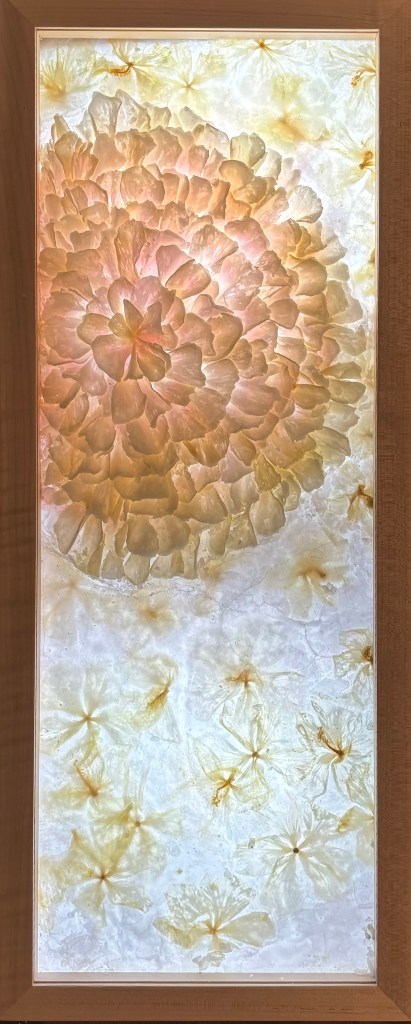

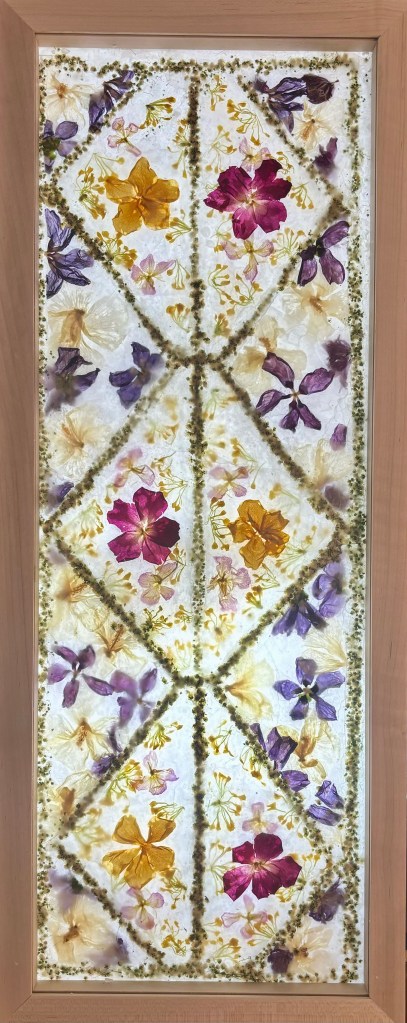

The Gardener/Garden

Silk fabric, english daisies, pansies, hibiscus, roses, gelatin, thread, glass, wood. 38 x 48 x 12 in. 2021.

Crushed Fragments

Hibiscus, roses, yucca seeds, daisies, garden greens, gelatin, dress fragments, glass, wood. 43 x 39 x 2.5 in. 2023.

Summer Garden

Hibiscus, azaleas, roses, marigolds, all collected over a one month time period from the artist’s garden, rabbit skin glue, cotton, thread, wood, glass. 43 x 43 x 2.5 in. 2023.

Crushed Tulips

Tulips, hibiscus, pectin, mixed cloth, thread, glass, wood. 43 x 43 x 2.5 in. 2022.

Pansy Pansy

Pansies, hibiscus, pectin, mixed cloth, thread, glass, wood. 43 x 39 x 2.5 in. 2022.

Beneath and Above the Paving Stones

Beneath and Above the Paving Stones was commissioned by the Oak Springs Garden Foundation in Upperville, Virginia. The piece honors friends of John F. Kennedy—Jacqueline Kennedy, Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon, Jean Schlumberger, and Sergeant James Felder—who made a memorial for his gravesite at the Arlington National Cemetery. Their memorial was never installed, eventually lost over time, and then recently recovered by the foundation.

The work, pictured here, is made from wax and dried flowers. Each panel is between two sheets of glass and wood in a pattern like the paving stones on Kennedy’s grave. Each panel represents these friends of JFK. As people came to mourn at his site, they left mounds of flowers and military caps to honor his passing. The flowers emphasize the fragility of time above the paving stones and the memories that lie beneath them.

Pieta

Mixed flowers, pectin, thread, chair, cotton, walnut husks, 41 x 25 x 22 in. 2020.

“As I draped the quilt over the lap of the chair, I couldn’t help but see Michelangelo’s Pieta: with Mary’s legs spread wide, supporting the sacrificial Christ. I contemplate the similarities I see in the quilt as something that was inevitably returning to dust. Beautiful and brilliant in colour, which will only be here for a short window of time.” -S.L.L.

Decomposing Quilt

YouTube link: https://youtu.be/UTfY5FoSYNw, 5:56 min video is projected onto a large quilted screen 66 x 48 in. 2022.

Decomposing Quilt, 2022, is a video of quilted squares made from soil and plant life materials collected from locations in the United States where the artist’s ancestors were born or died. Each site-specific quilt square was filmed as they decomposed over time. The individual squares were then stitched digitally into a blanket, moving back and forth between states of decay and rebirth in a continuous loop. The video is displayed on a sizeable quilted screen of cotton and wax.

Taming the Unruly

Dandelions, cottonwood seeds, thread, pectin, chair. 33 x 15 x 18 in. 2022.

This work is made of dandelions, cottonwood seeds, thread and pectin: all materials which are extremely difficult to shape and sew. While working on the quilt, it kept falling apart, as if it had a desire to burst its limits, just like a child who is coaxed to sit still in a mother’s lap. The various seeds used to create the work are designed not to remain dormant; they are restless and want to scatter, much like a child.

Where She Stood

Cotton, hanger, thread. Height varies, 2017.

Stepping Up

Cotton/poly blend fabric, Kool aid and hibiscus dyes, hangers, thread, 5 x 28 x 3 in. 2019.

Silhouette

Cotton fabric, acrylic, thread, hangers, 55 x 16 x 32, 2019.

Shell, Skin, Yolk

Egg shells, rabbit skin glue, egg yolks, dress, oil, soil, red ribbon, and other mixed media. 36”x24’x6, 2024.

Intertwined

Kool aid and hibiscus dyes, salt, fabric,, hangers, 60 x 17 x 7 in. 2019.

Pushing Against

Cotton/poly fabric, hangers, plaster. 65 x 21 x 7 in. 2019.

Pushing Against is a simple dress dipped in plaster. The dress does not stop at the knees or ankles. It transitions into a similar and smaller dress hung upside down. Stretched between two hangers, it embodies a mother and a daughter connected by an umbilical cord of fabric, fighting against gravity as it reworks itself down the wall. The dress is in the birth position, acknowledging their interconnectedness, yet that connection forces a change in both. Tied in a state that must transition over time, their ruin becomes their purpose, and their triumph fulfills their creation in this sublime moment of existence.